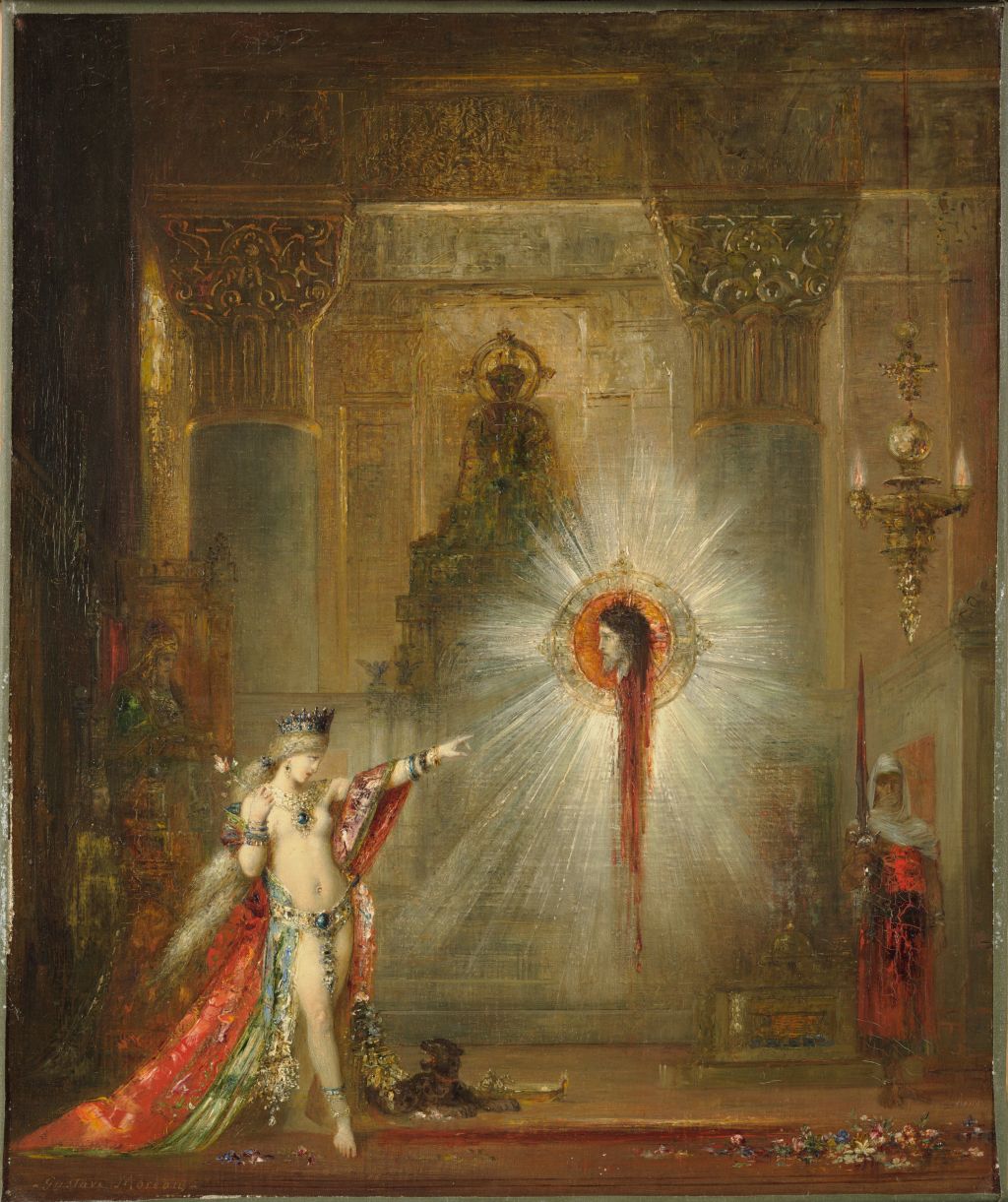

A lesser known painting of the 1800s is The Apparition by Gustave Mareau. While this painting and artist are prominent in their own right, they are overshadowed by the popularity of other artists like Monet. During this time, more academic art was out of style and more expressive art was in. Moreau responded to this shift by combining academic processes with mystical elements. He creates a piece that counters the popular art of his time while creating a spiritual drama.

The Academies at this time were steeped with tradition. They favored religious, historical, and ancient scenes. The styling and methodology of painting was rigid and critiqued for being “outdated.” When people think of art movements in the 19th century, they think of Impressionism, Realism, and Naturalism with artists like Monet, John Constable, and James Whistler. These new movements shifted from the religious or spiritual themes of academic art. It shifted away from the Historical, Neoclassical, and religious paintings of the academy. While they may comment on supernatural elements, they mostly depict the world through a natural lens. Farm life, prairies, and city streets are the subject matter of choice.

Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket by James McNeill Whistler

When the pendulum began to swing back, it came in the form of Symbolism, a movement that favored mysticism and romance. Gustave Mareau was a major figure in this movement as it pertains to visual art. As a response to the ordinary, Symbolism packs as much supernatural meaning and imagery as it can in its paintings while vailing it in some level of mystery. While naturalism suggests its message through a sunrise or a wheatfield, Symbolism wraps its message in the unordinary. The advantage to mysticism is that metaphysical messages, such as morals about virtue and vice, can be more directly discussed because it openly acknowledges the metaphysical world.

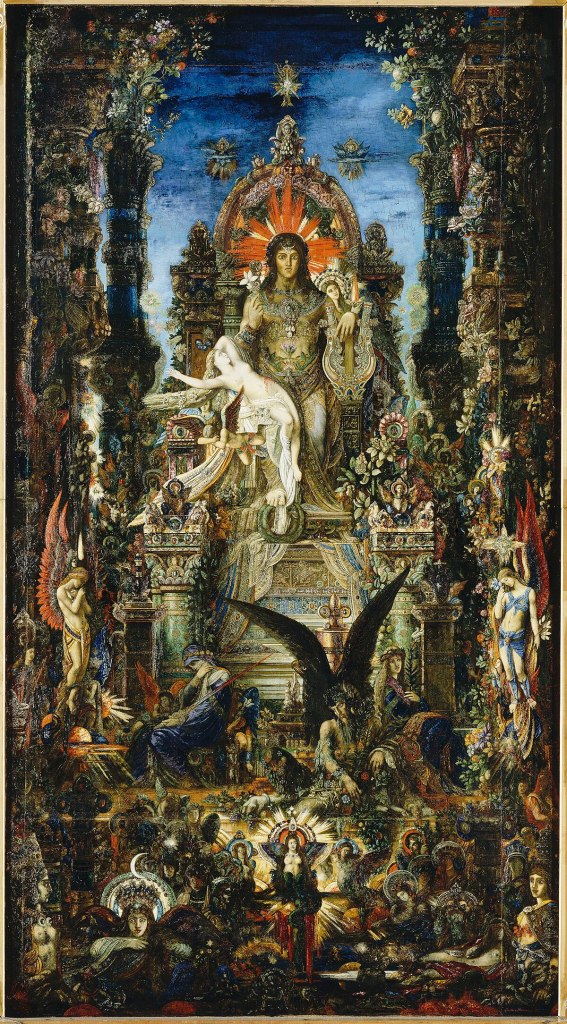

Moreau himself largely painted biblical or mythological scenes (such as Jupiter and Semele). He often combines western religion and mythology with Orientalism (the mimicking of the far East) to further accent the unfamiliar and spiritual feelings his paintings provoke. In his paintings the walls are adorned like a South Asian temple with dark shades of gold and teal. In the oil version of The Apparition, a large pagan idol looms in the background. Though heavily obscured, the general pose is similar to a statue of Buddha or a sitting deity.

Jupiter and Semele by Gustave Moreau

The Apparition was painted around 1876. It was painted several times, first in water and finally in oil on canvas which this article will focus on. The Apparition depicts a mystical scene of St. John’s decapitated head levitating immediately after his death. Salome stands pointing at the head with king Herod and her mother behind. This scene all takes place in a pagan temple with the aforementioned idol.

The two characters who take center stage are Salome and St. John. These two stand opposite from each other, dividing the painting into two sides. St. John’s halo radiates the most light in the scene. A large flow of blood pours from his head which gives him a sense of upwards ascension. A guard stands with the bloody sword of St. John’s martyrdom but his body is nowhere to be found. Additionally a large chandelier hangs down the right side of the painting.

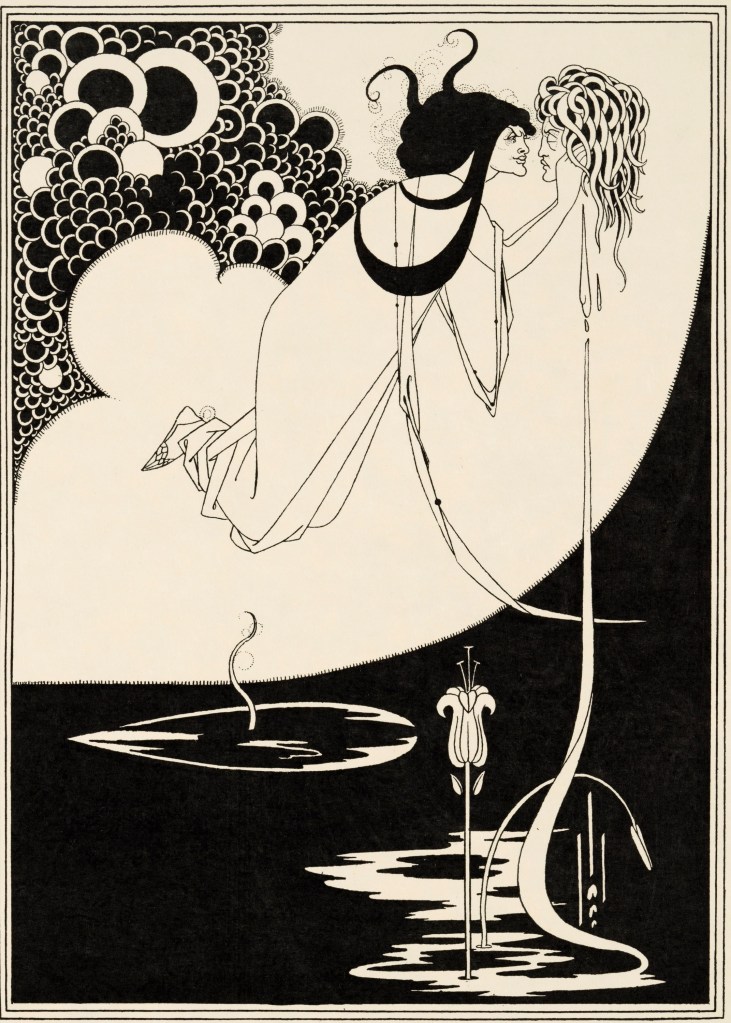

Salome appears several times in Moreau’s work, in all the versions of this painting and in Salome Dancing Before Herod which depicts a similar scene. In visual art she has become a symbol of the Femme Fatale, a character type for a seductive and dangerous woman. The Femme Fatale has taken on messages of woman empowerment, and also includes themes of perversion and subversion of cultural norms such as in Audrey Beadsley’s illustrations of Salome. As you will see, Gustave Moreau takes aim at all of these elements of the Femme Fatale in the Apparition. He recognizes the subversions, acknowledges the tension, and reverts the norm.

Salome and St. John by Aubrey Beardsley

Salome is the second most illuminated in the scene. The light reflecting off of her is in competition with the light emitting from St. John the Baptist. Notice that the light from St. John is not illuminating Salome but another light source hits her from the opposite direction. Salome doesn’t have a halo but wears a large crown and is loosely clothed in regal attire. Her underwear is adorned to draw attention to her crotch. A dog sits near her feet. Often, a dog in art is symbolic of lust.

Here Moreau draws the battle lines. On one side Salome stands self righteous. She is powerful by her own making. Though there is a pagan idol already in the scene, Salome makes herself more of an idol and challenges St. John the Baptist. On the left side we can see the outcome of her empowerment. While the dog, the lowest of creatures in the scene who represents lust, sits in worship, King Herod, who once worshiped her, is hunched over in his chair, enveloped in shadow. He lost all strength, and appears more dead than St. John. On the other side, St. John is levitating above Salome. Just prior, he was killed, seemingly ending this battle before it began. But now Moreau indicates that the beheading may have been more akin to Darth Vader killing Ben Kenobi, making him “more powerful than you could possibly imagine”. St. John’s body is nowhere to be seen. In other words, he is entirely free from the weaknesses of the flesh. The main weapon of the Femme Fatale is rendered useless against him.

The sword used to kill St. John is a significant detail. In Christian art, the means of death for saints is often depicted with them. Think of Saint Sebastian holding arrows which were used to kill him. These gruesome tools are sanctified by the saint that they killed. They represent faith in God and willingness to submit their lives to His Will. St. John accepted purgation and ultimately his own death. This bloody sword indicates he was willing to deny weakness. While King Herod wears an expression of exhaustion and Salome has an expression of aggression, St. John has a stoic expression. Rather than being destroyed by Salome like Herod, he’s unaffected by her. Moreover, he has become more powerful than her.

Traditionally, a lit candle or chandelier indicates God’s presence. The lit chandelier in this work illustrates how John was given this power.

What appears as a cryptic killing, Mareau sets as a battle between pleasure and suffering, between lust and chastity, and between powerseeking and selflessness. He characterises Salome as the Femme Fatale. Much like the rejection of naturalism, and realism, he rejects popular ideas of this character. His Femme Fatale inverts what other artists depict Salome as and shows that she grasps for power vainly. St. John, through submission, suffering and a realization that there is a supernatural reality, is able to transcend. This whole narrative is wrapped in mysticism inviting the viewer to reflect on spiritual realities more.

Leave a reply to romancatholicreveler Cancel reply